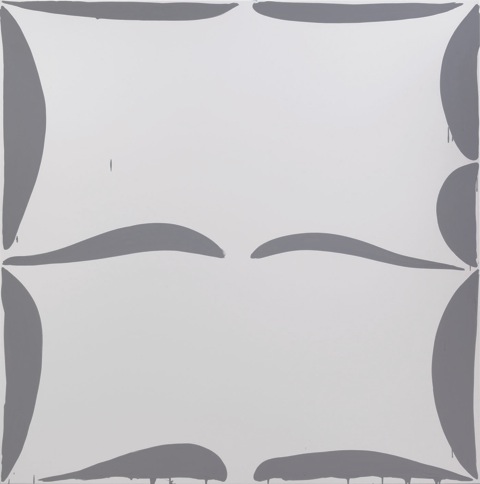

Amy Feldman, “Psych Alike,” 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 79 × 79″. Courtesy: Blackston Gallery, New York.

For this artist’s second solo exhibition at Blackston, the walls and ceiling of the front gallery have been painted gray, and the difference this makes in how one experiences the five large-scale paintings that explore the tonal shifts of the complex hue is significant. The usual neutrality and isolation of the white cube experience is diminished in favor of an enhanced and continued range of gray tones that separates the paintings but does not provide the jolt that white would have when looking from one painting to another. Each of the five paintings, however distinct from one another, exchanges aspects and elements—such as color, animated application of paint, and the rounded lines and shapes—freely. The direct and playful surety of the images is a result of retaining a near duplication of formal elements while being willing to invent and accept the byproducts of a performative approach to painting.

“psych alike” and “Open Omen” (both 2014) boast largely empty canvases with a number of scalloped and curved shapes that stick close to but don’t always touch the paintings’ outer edges. Brush marks and drips evince an unfussy precision and subtle asymmetry, suggesting a poised but out of kilter and rather comedic sense of balance. In “psych alike,” lighter gray shapes and two central, horizontal shapes that mimic a moustache establish a completely different feel; it is gentler in impact, less tense, an altogether different character though still part of the same family. “Open Omen” shares a similar charcoal color and centrifugal composition to “Gut Smut” (2014) but the shapes have become completely rounded, as if they have moved in from the edge to become more visible. Of course, this is not the case. Each painting is independent; it is the curious identifications that occur when confronted with such strongly related works that expose the formal logic—and humor—while not spelling out what this might signify. Not that explanations are necessary, for the “expression” that a painting possesses is here enigmatic and fun; think Buster Keaton’s face in close up.

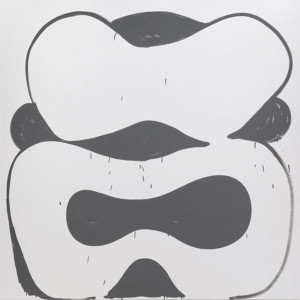

Amy Feldman, “Killer Instinct,” 2014. Acrylic on canvas, 79 × 79″. Courtesy: Blackston Gallery, New York.

“Gut Smut” echoes “psych alike” and “Open Omen” with its open center, its negative shape similarly sided with two curves on three sides, three on one side. The stacked pebble forms create a sort of frame, appearing to circle and turn, become oblique or frontal. The gray surface fluctuates between flat opacity and openly brushed internal gestures against the even pale gray ground. As with all the paintings here, the figure/ground relation is active and questioning, creating a kind of spatial ambiguity, especially from distance. It is obvious that the artist takes pleasure in the material aspects of painting, an approach not unlike Mary Heilmann’s; there is no “duking it out” as Heilmann put it, as there was for the Ab-Ex generation. Planning and preparatory drawings allow Feldman a spontaneity within limits that also leaves plenty of room for happy accidents or the occasional disaster. The process of revision and struggle over days or months that defined Ab-Ex is now a tightrope walk of one painting session.

n the back gallery, the walls of which are a darker gray than the first room, is a series of smaller paintings titled “Hour Triumphs” (2014) and “Popular Mantra” (2014), each comprised of a group of four canvases. Respectively, all share a formal closeness to one of the larger paintings present in the front space entitled “Killer Instinct” (2014). They collectively underline the apparently endless variations of seemingly minor displacements and adjustments. The two pieces read like freeze-frame moments in the evolution of an image, or the declaration that a definitive image is neither desired nor realistically possible. Each image might evoke anger, amusement, or exhaustion; some shapes seem to lean against the edge of the picture plane for support. The bold and swiftly constructed images are a product of staying within the traditional means of painting and not seeking out novel materials or techniques. Consequently, it may be surprising that painting can look so fresh and that an artist can find the means that she needs without looking further than paint, brushes, and canvas.

The potential idea of monumentality is easily undone by Feldman’s insistence on not using size or somber color as a prop for seriousness. Her sense of humor, cartoonish and punning, allows the urgency and immediacy of both idea and image to balance without becoming encumbered with the conceits of previous or current generations. As time passes, grouping artists together under categorical titles—can we see Robert Ryman as a minimalist now?—becomes less effectual, and artists like Feldman will outweigh their similarities to others with differences, every time.