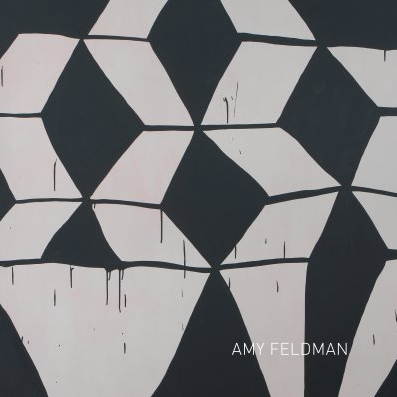

There’s a visual hit to our first encounter with an Amy Feldman painting, or better, a group of them. They telegraph their overall image structures across space like bold signage. Greenberg would have approved. Or, who knows? He might have found their traceries of the grotesque a bit icky: ok for Pollock, Louis, and Frankenthaler, maybe, but Feldman may just be a bit too cartoonal. For Greenberg, that meant Pop, “easy stuff” in his mind. But Feldman’s stretched and pulled geometries hint at a darkness that her stark and high contrast figure/ground relationships don’t dispel. What’s moving about in the shadows? The usual sex and death, cognitions that are generally hard on the intent to remain abstract, and invariably complicate easy formal ironies.

Feldman’s studio is by the elevated F train in Brooklyn, in an old manufacturing loft area

not too far from the Gowanus Canal. It’s a brutal stretch if you’re looking for greenery, but the kind of area artists love (there’s a Lowe’s next door). She describes the elevated tracks, which have been under long-term repair, as “ . . . very toxic and beautiful and bare-bones.”1. It’s an apt description of the emotional pitch of her paintings with two additions: they are also funny and sexy. Feldman has a gift for drawing with paint on a large scale. Her compositions seem big even in a small size, but her natural scale is a canvas half again as high, or long, as she is. This is a scale that addresses and virtually embraces our embodied gaze, pulling us into the illusionist space of her forms, or pulling her forms out into our own physical space.

What’s “toxic” about Feldman’s paintings is the way in which the scale of her forms gets up in our faces and the peculiar poison of her near black mixed greys, the color described by William Gibson in the opening line of Neuromancer, “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” But the toxicity is also funny, because it emanates from paintings that have the elegance of Rothko’s “tragic sublime,” Motherwell’s epically ridiculous Spanish Elegies,and Louis’s Bronze Veils

in their DNA. The only way to bring toxicity into the language of the beautiful is through a sense of humor and seductiveness. Feldman belongs to a generation that can love the “tragic sublime” from a distance that allows parody. And effective parody usually comes from love. We can see that this is a sexy love in the graphic fluidity of her paint.

So we’re confronted by Owed, an enormous pun wherein the large circular band whose outline grows little semicircle ridges of its own, like Little Orphan Annie’s ringlets in silhouette. It flattens on the bottom, like a Guston automobile tire. It’s a painting that goes boo and then tries to stifle its own laughter. It’s a vortex that asks you to stick your head in the center, from behind the picture plane. Pressure Points is a gigantic melting chevron in a wastebasket. Or maybe the thin, dark grey line isn’t a cross section, but the edge of a hanging cloth, as if an abstract image was burned into the Shroud of Turin. Or the Shroud was really a beach towel. In & Out is a rectangle target listing to one side the way barbershop mirror reflections eventually do, and also a dark door at the end of a mesmerizing hallway. The stacked triangles of Scrapple Still Life, create doubles in the off white “negative space.” It is a deeply rhythmic painting, deep as Jah Wobble’s bass. The lower right triangle appears to be giving birth to a grey-blue cloud in an Advent calendar window. The lower left triangle is just roughed in with long brushstrokes. The “white” is stained with ochre, like nicotine,. There are drips in all the paintings, daring

us to call them decoration or affective, when they are so obviously intrinsic to her seductive performance of painting.

Feldman paints with irony as a defense against the punishing naiveté of ideology, and she

is sincere about it. That is to say, her paintings know a lot, they have a lot of languages in

them, and they let us know what they know with startling economy of means and a necessary

theatrical grandeur.

1.Interview with Valerie Brennan in Studio Critical, August 9, 2011. http://studiocritical.blogspot.com/2011/08/amy-feldman.html